Fiction Unplugged: Matt Bondurant, An Introduction

Outside of cooking, reading, running, and Siggy, fiction is my thing. But part of writing fiction is accepting that most of it goes unnoticed (which is not a singular complaint). Fiction Unplugged is a series of work - widely-published, self-published, unpublished - that's typically gone unread.

Matt Bondurant: An Introduction

A few years back, I was asked to introduce a visiting writer before his reading at Boise State. It's a very small thing, an introduction, and often forgettable, but I was proud of what I put together (and so pleased when he took the mic and politely lied, "Wow, that's the, uh, that's...uh...that's the best introduction I've ever had").

If you’re the type who harbors literary aspirations, it’s normal to feel a few stabs of jealousy when you read about Matt Bondurant. Still shy of his fifth decade, he’s collected a host of scholarly letters, the latest a PhD in Creative Writing from Florida State, and has become something of a specialist in –ships and –cies (that being fellowships and residencies to you non-literary folk). This includes fellowships at Bread Loaf, Florida State, and Sewanee, and residencies at Yaddo and the MacDowell Colony. Bondurant has appeared on Radio France, NPR and The Discovery Channel and has graciously lent himself out to dozens of literary festivals, workshops and conferences.

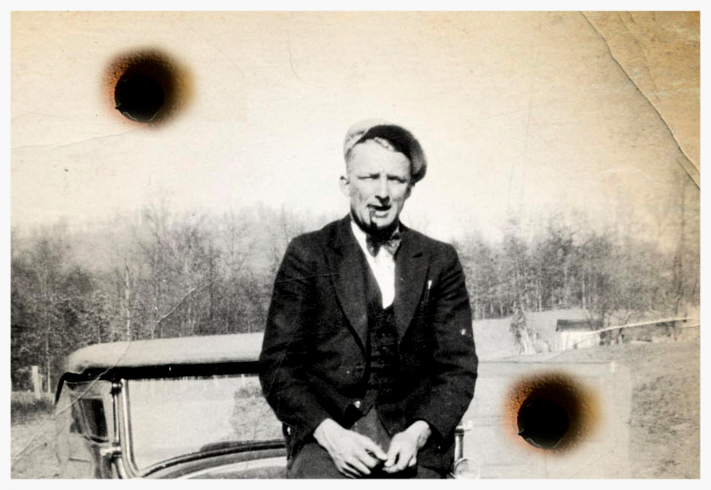

Then there’s his writing. In less than a decade, Bondurant has published three substantial novels: The Third Translation, an international bestseller which, belying its title, was translated into fourteen languages; The Wettest County in the World, a novel based upon the bloody events of his own grandfather and great-uncles’ storied career manufacturing mountain dew in the hills of Franklin County, Virginia; and his latest, The Night Swimmer, a novel about marriage, Irish pubs, and open-water swimming, which has been compared (favorably) to the work of John Cheever (a favorite of mine). Filling the holes between the novels, Bondurant’s short fiction, poetry, literary reviews and essays have appeared in Glimmer Train, Prairie Schooner, The Notre Dame Review, The Southeast Review, and the San Francisco Chronicle (among many other outlets).

After my first exposure to Bondurant – blowing through The Wettest County in the World in a few, short days – I have my own reasons for feeling envious of him. It’s not only that he had a delicious story buried in his family’s past he could excavate, study, reassemble and, like a skeleton in the hands of a mad scientist, reanimate. It’s not only that he gave life to a story only heard in local bars, read in stodgy court documents, and alluded to by people who were there (or were old enough to at least lie about being there). It’s not even his family name, Bon-dur-ant, which rolls slowly around your mouth like a steely, coated in caramel. Rather it’s his rare ability to write about characters haunted by their own shadows. In The Wettest County in the World, that ghost frequently appears at the bottom of a Mason jar, the plain, clear receptacle at the heart of so much of the novel’s violence, yearning, and heartbreak. Here’s one of those beautiful moments, where the giant Howard Bondurant (Matt Bondurant’s great-uncle) is standing in the kitchen, talking with his wife Lucy:

“I’m going out for a bit,” Howard said.

“Howard,” Lucy said. “There’s only so much liquor to drink.”

She rocked the baby gently.

“It’ll never be enough,” she said.

“I’ve got plenty set aside,” he said.

Lucy stared at him, her eyes saucers of limpid blue, the baby nestling at her neck. Howard looked out the front window. On the porch, the luna moths clustered, throwing their furry bodies against the window glass.

“One day,” she said, “that jar’ll be empty and nothing you can do about it.”

“Not if I can help it.”

“Oh, Howard,” Lucy said, “how much liquor is there in this county? In the world?”

“Might try to find out,” Howard said, and stepped out.

It’s strange and still somehow comforting to read about emptiness, about a jar that’s never quite full enough. Maybe the comfort is knowing we’re not the only person who suffers from that self-inflicted wound, that hangover, that tendency towards “manufactured discontent.” This is the target, I suppose, of all great stories, and it’s a target which our guest tonight has struck multiple times.

Ladies and gentleman, please welcome Matt Bondurant.